Without the Industrial Revolution, there would be no modern agriculture, no modern medicine, no climate change, no population boom. A rapid-fire series of inventions reshaped one economy after another, eventually affecting the lives of every person on the planet. But exactly how it all began is still the subject of intense debate among scholars. Three economists, Raouf Boucekkine, Dominique Peeters, and David de la Croix, think population density had something to do with it.

Their argument is relatively simple: The Industrial Revolution was fostered by a surge in literacy rates. Improvements in reading and writing were nurtured by the spread of schools. And the founding of schools was aided by rising population density.

Unlike violent revolutions where monarchs lost their heads, the Industrial Revolution had no specific powder-keg. Though if you had to trace it to one event, James Hargreaves’ invention of the spinning jenny would be as good as any. Hargreaves, a weaver from Lancashire, England, devised a machine that allowed spinners to produce more and better yarn. Spinners loathed the contraption, fearing that they would be replaced by machines. But the cat was out of the bag, and subsequent inventions like the steam engine and better blast furnaces used in iron production would only hasten the pace of change.

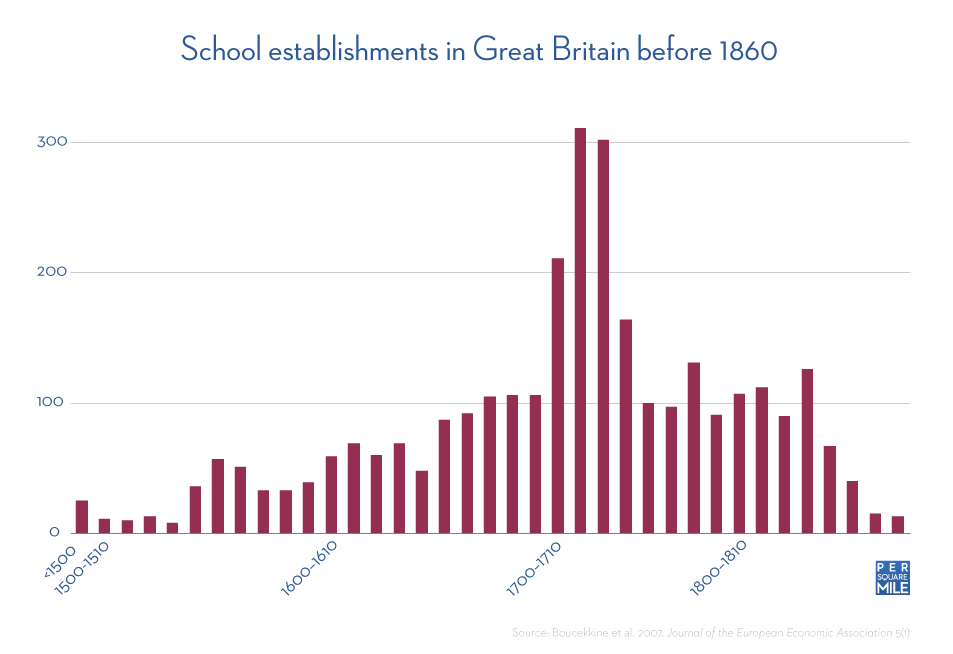

This wave of ideas that drove the Industrial Revolution didn’t fall out of the ether. Literacy in England had been steadily rising since the 16th century when between the 1720s and 1740s, it skyrocketed. In just two decades, literacy rose from 58 percent to 70 percent among men and from 26 percent to 32 percent among women. The three economists combed through historical documents searching for an explanation and discovered a startling rise in school establishments starting in 1700 and extending through 1740. In just 40 years, 988 schools were founded in Britain, nearly as many as had been established in previous centuries.

The reason behind the remarkable flurry of school establishments, the economists suspected, was a rise in population density in Great Britain. To test this theory, they developed a mathematical model that simulated how demographic, technological, and productivity changes influenced school establishments. The model’s most significant variable was population density, which the authors’ claim can explain at least one-third of the rise in literacy between 1530 and 1850. No other variable came close to explaining as much.

Logistically, it makes sense. Aside from cost, one of the big hurdles preventing children from attending school was proximity. The authors’ recount statistics and anecdotes from the report of the Schools Inquiry Commission of 1868, which said boys would travel up to an hour or more each way to get to school. One 11 year old girl walked ten miles a day for her schooling.

Many people knew of the value of an education even in those days, but there were obvious limits to how far a person could travel to obtain one. Yet as population density on the island rose, headmasters could confidently establish more schools, knowing they could attract enough students to fill their classrooms. What those students learned not only prepared them for a rapidly changing economy, it also cultivated a society which valued knowledge and ideas. That did more than just help spark the Industrial Revolution—it gave Great Britain a decades-long head start.

Sources:

Boucekkine, R., Croix, D., & Peeters, D. (2007). Early Literacy Achievements, Population Density, and the Transition to Modern Growth Journal of the European Economic Association, 5 (1), 183-226 DOI: 10.1162/JEEA.2007.5.1.183

Stephens, W. (1990). Literacy in England, Scotland, and Wales, 1500-1900 History of Education Quarterly, 30 (4) DOI: 10.2307/368946

Related posts:

Hidden cost of sprawl: Getting to school

Hunter-gatherer populations show humans are hardwired for density

Do people follow trains, or do trains follow people? London’s Underground solves a riddle

Photo scanned by pellethepoet.