Tucked amidst acres of asphalt jungle are cities’ unsung environmental heroes. Yards, lawns, gardens—call them whatever you please—these bits of unpaved earth play a real role in supporting thriving urban ecosystems. And they could play the part even more eloquently if we thought of them as parts of a larger whole.

Anyone who has spent more than five minutes in a city knows they are not always welcoming to people, let alone plants and animals. It’s common to see thin, scrappy weeds straining against their concrete binders, or birds clinging to wiry utility lines in lieu of more customary branches and brambles. But behind houses, or even hidden out front in plain sight, are postage stamps of possibility. With all the clipping, prodding, and spraying these diced green patches receive, it’s easy to forget that they are part of a real ecosystem.

Cities have long been overlooked by ecologists, mostly because the logistics involved in studying them can be convoluted. Getting permission from dozens, even hundreds of landowners is one of the biggest headaches, so urban ecologists typically resort to the next best thing—parks, forest preserves, greenways, and so on. Parks can be fantastic reservoirs of habitat, but their area pales in comparison to the amount of land scattered throughout the city as yards and gardens. Real urban conservation plans needs to account for everyone’s little patch of nature.

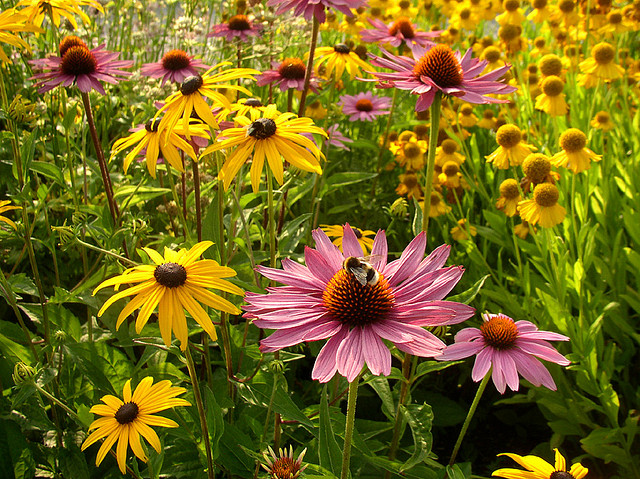

Here’s where landscape ecology can help. Landscape ecology teaches us to look beyond—or within—the various bits and pieces, components and parts that make up an ecosystem. Scale is king in landscape ecology, be it spatial or temporal. In the context of a city, this means that each individual yard and garden—which on its own can seem hopelessly small, only able to support a salamander, some insects, and a few birds at best—is just one piece of a larger patchwork, one connected by birds that fly across town, salamanders that waddle beneath fences, bees that hum between flower beds, and seeds that disperse on the wind. Protecting them all is only possible when conservation plans cover the gamut of spatial and temporal scales.

Unfortunately, much of this potential has yet to be tapped. By and large, cities remain natural wastelands. Habitat fragmentation keeps down the abundance and diversity of species. Inspired landscaping can counter the diversity problem, but it usually does so with exotic species that are poor ecological substitutes for natives. Pets—especially cats—take a toll on native animal populations, while air, light, and sound pollution add further disruptions to an already taxed ecosystem.

Still, most cities have enough material for a solid conservation foundation. Many people are earnestly invested in their yards, carefully curating selections of grasses, trees, and shrubs, attracting musical entertainment through bird feeders, and in doing so supporting a diversity of mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates. This has all been accomplished without significant coordination. Programs like the Audubon Society’s “Audubon at Home” or the National Wildlife Federation’s backyard certification scheme have nibbled at the edges, but lots more could be done.

A recent review of the landscape ecology of gardens suggests that to encourage habitat friendly yards and gardens a bottom up approach would be best. Top down programs can help cities meet conservation targets, but they do little to change people’s attitudes. Encouraging a “conservation ethic of the city” would probably be more successful, but also more difficult to engender. Lawn culture is heavily embedded in many Western nations, especially the U.S. and Canada. Lawns will always have their place; besides recreation, they are surprisingly productive ecosystems. Yet most are far larger than they need to be. Substituting appropriate plantings for classic Kentucky bluegrass would save people time and effort, reduce emissions from mowing, and boost habitat diversity and complexity.

Lawns are just one part of the equation. Landscape ecologists can step in to identify the driving forces behind landowner decisions. Where the conservation ethic exists, ecologists can encourage neighbors to coordinate their landscaping, clumping their native plantings so that four quarters can add up to one whole, for instance. Depending on the area’s ecology, landscape ecologists can further define optimal sizes for these native plots—for example, will it take twenty percent of four yards or six to meet the needs of a native bird? Or in other cases, water features like ponds may be more important than contiguity. Each city, even neighborhood, will have its own gestalt, and landscape ecologists can help discover it.

Sources:

Falk, J. (1976). Energetics of a Suburban Lawn Ecosystem Ecology, 57 (1) DOI: 10.2307/1936405

Goddard, M., Dougill, A., & Benton, T. (2010). Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 25 (2), 90-98 DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.016

Related posts:

Plants rockin’ the suburbs, animals not so much

Photo by Per Ola Wiberg.